Stolen Stage: The Untold Origins of What Denver Won’t Tell You About Red Rocks

Red Rocks: Where the Stones Remember

Before the music, there were myths. Red Rocks Park, carved by time and once walked by ancient tribes, became the dreamscape of inventors, rebels, and showmen. John B. Walker saw titans in the stones; the government saw a park worth claiming. Through conflict, fire, and forgotten railways, it was reshaped—its red cliffs now echoing with rock anthems and the ghosts of visionaries. What looks like natural perfection is also a tale of ambition, erasure, and reinvention. Today, Red Rocks stands not only as a stage for sound, but as a monument to the strange and storied path of progress.

The Red Rocks Park has a deep and fascinating history, one that stretches from ancient Paleo-Indian inhabitants to today’s world-famous concert venue. Long before any development, this stunning region of Colorado’s Front Range was home to Indigenous peoples, including the Clovis and later the Woodland Indians—specifically a group known as the Lodeska Tribe. In time, the Ute Mountain Tribe also became stewards of this sacred land.

After Native American tribes were forcibly removed, early settlers renamed the area “Garden of the Angels.” By 1875, the nearby town of Morrison was founded, and visitors could take the Denver, South Park & Pacific Railroad to town, rent a donkey, and ride into the hills to picnic and marvel at the views.

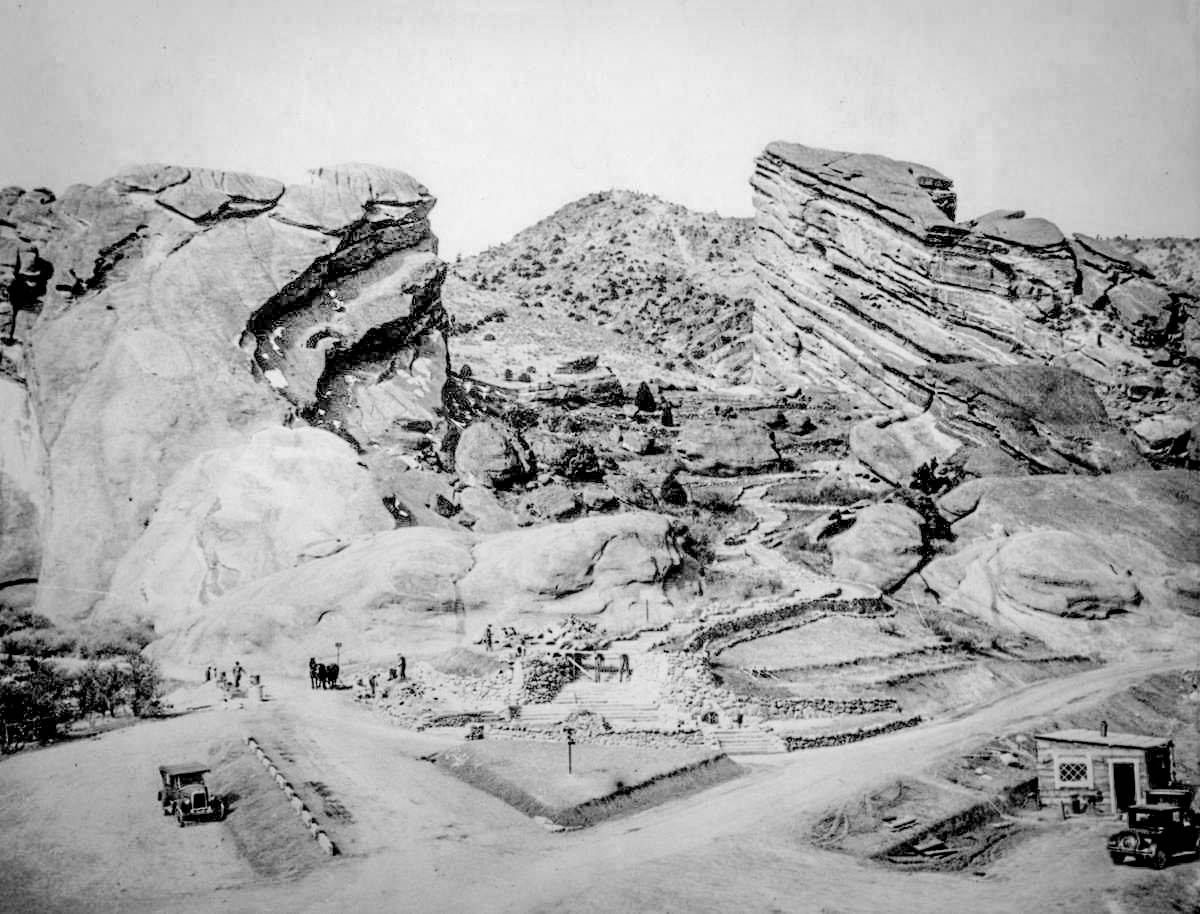

One of the first major developers of the area was entrepreneur John B. Walker, who envisioned a resort-style attraction with a funicular (a cog-driven incline railway) leading up Mt. Morrison. He dubbed it the “Garden of the Titans,” building scenic pathways and dramatic rock features to evoke mythic grandeur. Unfortunately, Walker’s ventures faltered after his nearly completed mansion on Mt. Falcon was struck by lightning and burned down. Financially overextended, he was forced to sell the land.

In the 1920s, Walker sold the property to John Ross and the Bear Creek Development Corporation. Ross—brother of Harold Ross, founder of The New Yorker magazine—had grand plans of his own. With Harold’s financial help, they renamed the land “Park of the Red Rocks” and began ambitious developments, including a hydroelectric dam project in Bear Creek Canyon. Evidence of this forgotten effort still remains: a concrete dam and a diverted river path, rarely acknowledged in official accounts.

Yet this development caught the attention of the City and County of Denver. Allegedly alerted by a disgruntled Walker, the city claimed the construction was unsafe and launched a legal condemnation process. Though Denver maintains it purchased the land from Walker for $54,133, there is no record of such a transaction in county archives. The truth, buried in the case of John Ross vs. The City and County of Denver, suggests that eminent domain was used to seize the land from Ross and Bear Creek Development—a story often omitted from Denver’s official histories.

Following the City of Denver’s seizure of the property, development plans shifted toward public use. In 1925, Denver began acquiring land throughout unincorporated Jefferson County to create what would become the Denver Mountain Parks system. The idea was to provide scenic recreation spots that could be accessed by a growing number of automobile tourists, especially those drawn to Colorado’s reputation as a health destination—particularly for tuberculosis patients seeking the region’s dry climate.

Denver’s vision mirrored that of Colorado Springs’ iconic Pikes Peak. The goal was to create a local equivalent—drawing travelers westward to marvel at the mountains by car. Roads to Mount Evans (now Mount Blue Sky) and the scenic Lariat Loop were part of this infrastructure expansion. Meanwhile, John B. Walker had banked heavily on steam-powered cars like the Stanley Steamer, which ultimately failed to gain mass popularity, contributing further to his financial downfall.

Denver’s use of eminent domain in acquiring Red Rocks was officially justified by concerns over structural safety. City engineers claimed that Walker’s original constructions—stone walls and entrance ways made from rounded river rock—were unstable. But many historians believe this was a convenient excuse to justify condemnation and acquisition of valuable land without fair compensation.

Despite these controversies, the result was a remarkable transformation. In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, the Federal Government partnered with the City of Denver through New Deal programs. A Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp was established in Morrison, one of the few fully intact CCC sites remaining in the United States today. Workers from the CCC and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) were instrumental in shaping the Red Rocks Park we know today.

Urban planner George Cranmer, along with Denver architect Burnham Hoyt and famed landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., envisioned a natural amphitheatre carved into the stunning red rock formations. The result was the iconic Red Rocks Amphitheatre, which officially opened in 1941. Denver Mayor Benjamin Stapleton—a controversial figure due to his known affiliations with the Ku Klux Klan—was also instrumental in pushing the project forward during his tenure.

As Red Rocks Park evolved, so too did its names, stories, and features—sometimes celebrated, sometimes erased. One of the most iconic landmarks, originally named Ship Rock by John B. Walker, was so called for its resemblance to the sinking stern of the Titanic. Walker even added a metal handrail to a stairway carved into the rock, allowing visitors to climb to the top and imagine themselves on the bow of a great ship. This dramatic staging gave rise to the park’s mythic title, “Garden of the Titans.”

However, in recent years, the City of Denver has quietly reverted the rock’s name back to Creation Rock, its earlier designation from the “Garden of the Angels” era. This name change has sparked criticism among historians and locals who view it as an erasure of Walker’s original vision and early 20th-century development history. Interestingly, Ship Rock remains labeled as such on official U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) maps and in Jefferson County courthouse records, even as the city rebrands it.

Walker’s dream of attracting tourists to the summit of Mt. Morrison also included a one-of-a-kind Funicular railway, which he promoted as a “railroad” to avoid confusing the public with the unfamiliar term. In truth, it functioned more like a modern roller coaster—a cog-driven ascent offering breathtaking views of the Front Range. Though the funicular is now long gone, its story lives on in tales of early amusement rides and daring engineering feats.

After Denver’s acquisition, many of Walker’s original structures and enhancements were either removed or repurposed. The iconic metal railing atop Ship Rock was dismantled, and safety concerns ended the era of casual climbing on the rocks. Today, climbing on the formations is strictly prohibited—violators face fines of up to $999.

But the park remains a beloved space for hiking, biking, photography, and education. With concert ticket prices rising, the free access to the park during daytime hours offers a priceless opportunity to explore a geological and cultural treasure nestled in the Colorado foothills.

Today, Red Rocks Park is not only a world-renowned music venue but also a living monument to America’s natural and cultural history. Its unique convergence of geology, architecture, and storytelling makes it a singular destination in the West—and a complex one.

One of the park’s most overlooked treasures is the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp in Morrison. Built in the 1930s, this site remains the only intact CCC camp of its kind in the country. Despite its significance, the camp was closed to the public for decades. It wasn’t until 2018 that the Denver City Council voted to fund its restoration and open it as an interpretive center for visitors, historians, and students of the New Deal era.

The long delay in gaining recognition for the CCC camp—and for much of Red Rocks’ layered history—has led many to question the city’s historical narrative. For years, Denver had not completed the necessary filings for the park’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places, a curious omission for a site of such national prominence. Fortunately, that has now been corrected.

The efforts to restore and reinterpret Red Rocks are part of a broader cultural reckoning. Just as the park’s natural features have undergone slow geological change, so too has public understanding of its human past—Indigenous stewardship, settler ambition, forgotten visionaries, and government intervention. Even Governor Evans, namesake of nearby Mt. Evans (now renamed Mt. Blue Sky) has come under scrutiny for his role in the Sand Creek Massacre, prompting Colorado to reexamine how it names and narrates its landmarks.

As we move deeper into the 21st century, Red Rocks continues to serve not just as an entertainment venue but as a classroom of art, spirit, and science. Its red sandstone walls echo with the footsteps of ancient peoples, the tools of CCC workers, and the sounds of countless musicians. It is a place where history, myth, nature, and memory converge—and where the full story is still being uncovered.

Post navigation

T. Johnson © 2025 all rights reserved.